Pushing back against "comfortable silence"The Pittsburgh Foundation supports and amplifies community voices by using the arts as a force for social change. The “Psalms for Mother Emanuel” poetry project honors the victims of the July 2015 church massacre in Charleston, South Carolina, while igniting local dialogue about race relations and violence.

Artist Vanessa German’s mixed-media artwork includes a newspaper clipping with a blue wave and water droplets painted on bottom of paper.

IN THE BASEMENT OF THE EMANUEL AFRICAN METHODIST Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, Myra Thompson gave her final lecture on the Gospel of Mark. A beloved and faithful member of “Mother Emanuel,” as the church is sometimes known, Thompson had prepared an edifying discussion of perseverance and faith for her Wednesday-evening Bible study group. It focused on Mark Chapter 4—a story of a farmer planting seeds across his land. Though most of his soil is difficult, the farmer’s few good seeds produce enough sustenance to make his hardships worthwhile.

For some, the parable represents the powerful presence of good in the face of overwhelming evil. It’s a lesson that the congregation of the South’s oldest African American church would return to again and again in the heartbreaking time that would follow for Charleston and the rest of the country.

For on the evening of June 17, 2015, a self-proclaimed white supremacist entered the church during Thompson’s discussion, fatally shooting her and eight others.

The massacre sparked nationwide mourning, debates over the state of race relations, and proclamations against further violence. In the wake of the shooting, President Barack Obama denounced the “comfortable silence” that often follows such tragedies: “Once the eulogies have been delivered, once the TV cameras move on, to go back to business as usual,” Obama said, “[is] what we so often do to avoid uncomfortable truths about the prejudice that still infects

our society.”

Though the Charleston massacre happened hundreds of miles from Pittsburgh, our region’s community foundation has decided to break the local silence.

“The idea that [the congregation’s] gesture of fellowship could be met with such virulent hatred felt beyond the pale,” says Germaine Williams, The Pittsburgh Foundation’s senior program officer for Arts and Culture. In response to the tragedy, the Foundation commissioned renowned Pittsburgh poets Tameka Cage Conley and Yona Harvey to co-edit “Psalms for Mother Emanuel: an Elegy from Pittsburgh to Charleston,” a memorial poetry chapbook that honors the victims of the massacre.

The chapbook features the work of nine black poets, symbolic of the nine churchgoers who lost their lives. The writers are both established and emerging: alongside Conley’s and Harvey’s contributions, the chapbook contains work by Cameron Barnett, Liberty Freda, Vanessa German, Terrance Hayes, Sheila Carter Jones, Kelli Stevens Kane, Joy KMT and Alexis Payne.

“The shooter targeted folks who meant something to everybody,” Conley says. “So it wasn’t just family members or church members impacted by the shooting. It was the whole community.” Conley says she admires the Charleston congregation because they welcomed anyone—even those who hated them.

Her contribution to the chapbook reflects this openness: When the preacher says, the doors of the church are open, he does not mean to tell you what you already know: you can walk into any open door you please.

Terrance Hayes, a professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and recent recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, says that the chapbook’s poems are complex and heartfelt, going far beyond simply condemning the shooter. They grapple with what Stephanie Boddie, a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Mellon University’s Center for African American Urban Studies & the Economy, identifies as historical “strains of race hate, intimidation and terrorism that seek to undermine the country’s oldest Black-owned and controlled organizations.”

“That, to me, is more interesting than saying, ‘[The shooter] shouldn’t have killed them,’ ” Hayes says.

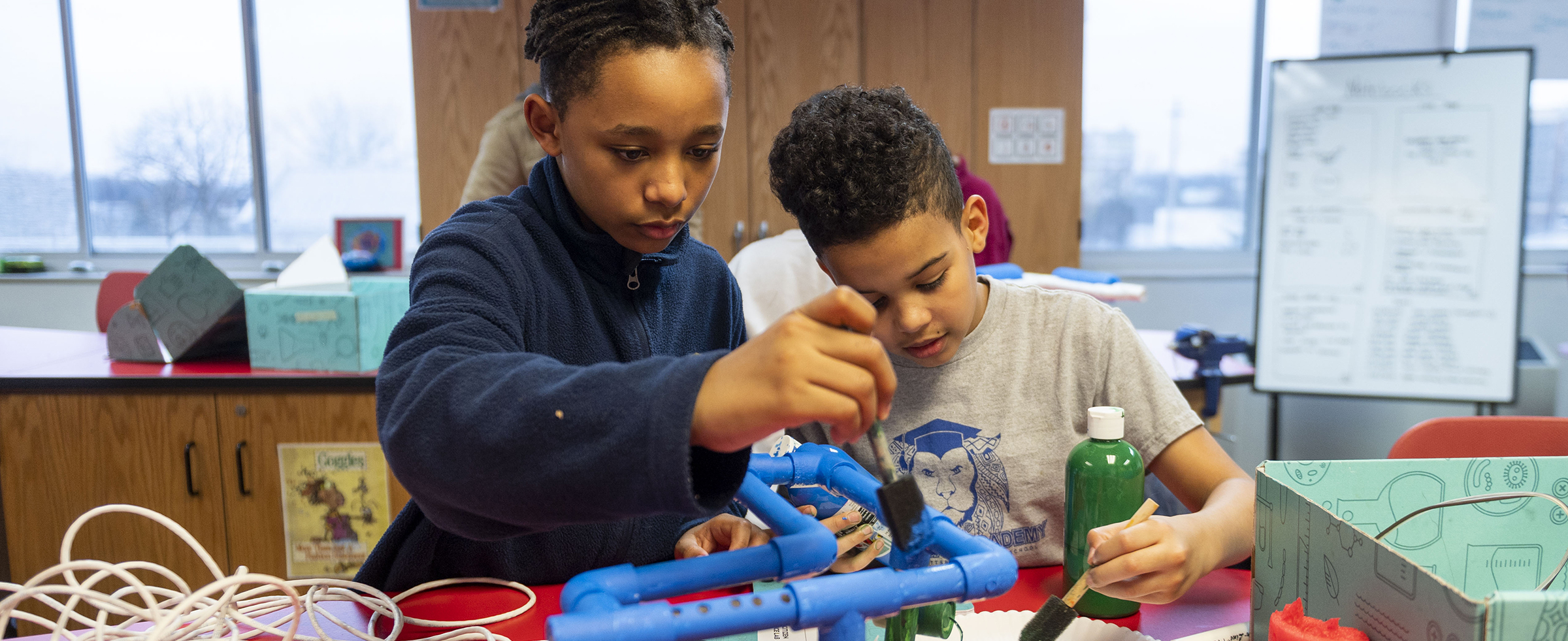

In addition to the chapbook, the Foundation and the featured writers are planning a series of community events designed to bring people together and spark public discussion of the poets’ work. “We’re looking to create a public space for dialogue and greater understanding of racial issues,” Williams says. “As a collection of powerful voices, ‘Psalms for Mother Emanuel’ is a way to spark discussion about the impact of racial violence both locally and nationally.”

When the preacher says, the doors of the church are open, does not mean to tell you what you already know: You can walk into any open door you please.

Tameka Cage Conley, Co-Editor, "Psalms for Mother Emanuel"

That discussion is essential, according to Rev. Carey A. Grady of Reid Chapel AME Church in Columbia, South Carolina, who wrote the chapbook’s foreword: “The Emanuel 9 Massacre broke my heart and the hearts of many people,” he writes. “The Pittsburgh community felt the depth of this tragedy and offered these psalms, laments, poems for us. In times like these, we need various forms of comfort that will spark introspection and help us come together as a human family to be better than we were yesterday.”

Download a copy of the chapbook, "Psalms for Mother Emanuel"

Original story appeared in the 2015-16 Report to the Community