Engineering a cureMedical researchers and donors come together to develop ways to fight a dreaded disease.

Assistant professor of otolaryngology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Dr. Umamaheswar Duvvuri calls flexible robotic system–aided procedures “the next revolution in surgical advancements.”

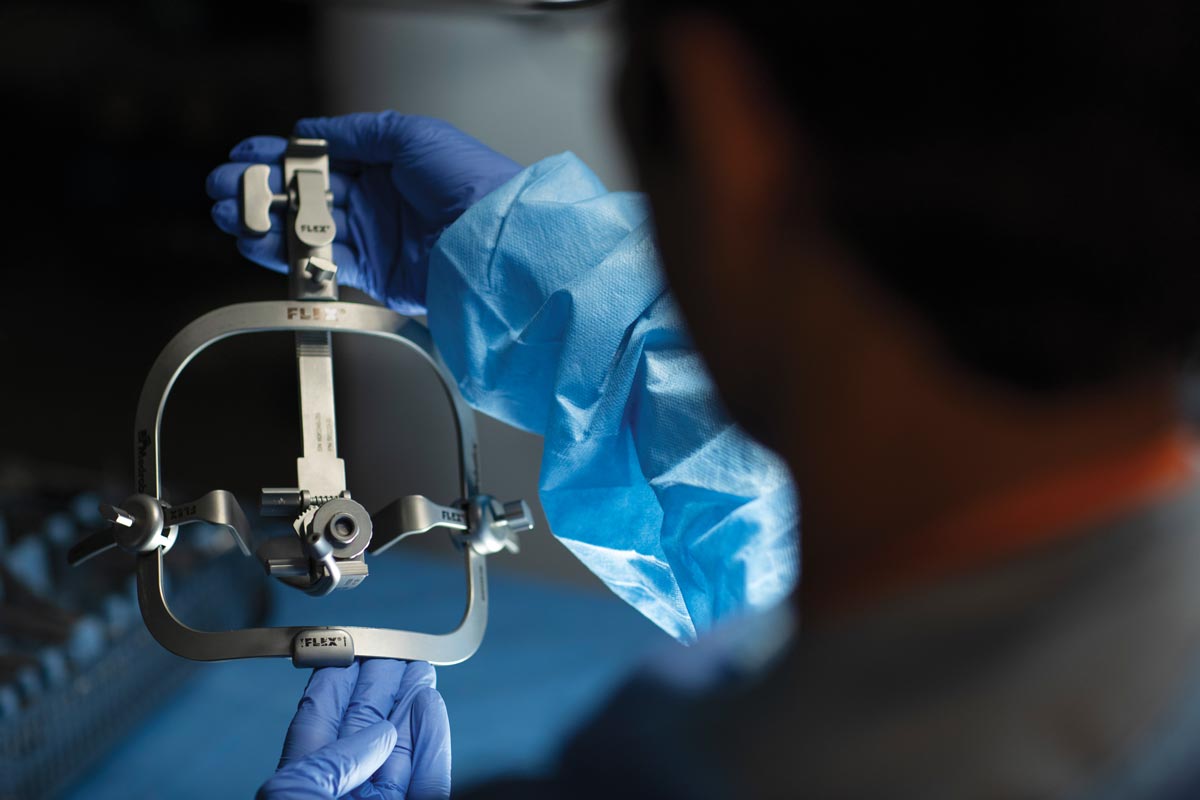

INSIDE A LAB AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH MEDICAL CENTER’S Eye & Ear Institute in Oakland, Dr. Umamaheswar Duvvuri stands over a life-size medical manikin and inserts a long, thin rod into its mouth. He wiggles the flexible tube — a robotic arm — and then takes it out again. It’s too wide to pass through the throat and down the esophagus, but that’s not a problem. The trial-and-error process is part of fine-tuning the design.

As a surgeon, Duvvuri trusts one pair of tools more than any other — his hands. And yet, he is all too familiar with their limitations, which is why he is leading an initiative that will allow him to operate without touching his patients. It’s all about robot technology, and the procedure he is developing promises a less invasive, more effective way to treat patients who have deadly esophageal cancer.

To aid this cutting-edge research, The Pittsburgh Foundation has given $100,000, matched by another $100,000 from the Foundation’s Myers Family Foundation Fund (a donor-advised fund) to Pittsburgh Collaborative Research Education and Technology Enhancement in Surgery (CREATES).

The esophageal cancer project is one of many at the institute that focuses on research, training and innovation for developing minimally invasive, advanced surgical technologies.

When cancer strikes the esophagus — the muscular tube that runs from the mouth to the stomach — survival statistics are grim, and treatment options are limited. Using the conventional approach, surgeons cut into the chest cavity, avoiding the heart and other vital organs while removing the diseased segment of the esophagus. The patient is left with a shortened esophagus and a list of serious complications, ranging from salivary leaks and digestive issues to infections and loss of speech due to nerve damage.

“It’s disruptive,” says Duvvuri. “It’s sort of like digging up your whole backyard to fix a broken water pipe. Now, wouldn’t it be neat if you could go through your faucet with a little camera and thread it backwards to get to the busted pipe? That’s the concept we’re trying to put forward with flexible robots.”

Duvvuri is using the Flex® Robotic System, developed by Carnegie Mellon University and its spinoff company, Medrobotics Corp. As an engineer, head-and-neck surgeon and medical director of Pittsburgh CREATES, he helped modify the Flex® robot for FDA-approved applications for surgeries on eyes, ears and nose. Now, he is working to modify the probe for a longer trip into the esophagus. In the operating room, Duvvuri often collaborates with surgeons who specialize in esophageal procedures, and for this new robotic frontier, he is working with a specialist, Dr. Inderpal Sarkaria, director of Robotics Thoracic Surgery at UPMC.

The snake-like Flex® Robotic System provides surgeons with visualization and noninvasive, single-site access to hard-to-reach anatomical locations to shorten recovery times and reduce scarring and risk of infection.

The Flex® robot is designed to be pliable yet rigid, making it ideal for this type of noninvasive surgery. “It’s like a snake,” says Sarkaria. “We hope these robots will enable us to do a better and more technically precise job and offer minimally invasive approaches to more patients.”

The technology may completely change the way a surgeon goes about removing a tumor from the esophagus. Instead of standing over a patient and reaching into the chest cavity with their own hands, surgeons will stand away from the operating table and use a joystick on a console to control the movement of the probe. “You can open and close your fingers like a pincer and grab something and pull it up,” says Duvvuri, demonstrating the process.

“Movements of the joystick can translate into precise movements of the instrument inside the body, but like driving a car, proficiency requires practice,” says Max A. Fedor, executive director of Pittsburgh CREATES.

"Ideas can come from everywhere. It’s not top down. Pittsburgh CREATES puts engineers and researchers together so that life-saving tools and techniques get to the market quicker."

--KELLY URANKER, Center for Philanthropy

Dr. Eugene Myers, former chairman of the department of otolaryngology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and founder of the Myers Family Foundation Fund at The Pittsburgh Foundation, says that during his 40-year career, he has always searched for promising surgical innovations. Now, by teaming up with The Pittsburgh Foundation, he is helping to fund the next generation of technology. “We can do a lot with the Flex® robot as far as minimizing the extent of surgery procedures,” says Myers, who also volunteers at Pittsburgh CREATES.

Once Duvvuri completes the next step in the process — working with a manufacturer to fine-tune the shape of the robotic arm so it reaches the esophagus — he will move on to testing the procedure on cadavers before seeking FDA approval.

Kelly Uranker, director of the Foundation’s Center for Philanthropy, says the promising new surgical research fits with the Foundation’s philosophy of funding innovations developed in the field. “Ideas can come from everywhere. It’s not top down. Pittsburgh CREATES puts engineers and researchers together so that life-saving tools and techniques get to the market quicker.”

In addition, working with industry leads to solutions that are cost-effective. As Fedor puts it, “While we are saving lives and reducing morbidity, we are also saving costs and time.”

LESSON LEARNED: While the technologies are innovative and being developed and adapted, the main drawback is time. The process from the idea to applied reality can take many years. This innovate-as-you-go model expedites that process.

Original story appeared in Report to the Community 2017-18